Plant Cell Structure

Plants are unique among the eukaryotes, organisms whose cells have membrane-enclosed nuclei and organelles, because they can manufacture their own food. Chlorophyll, which gives plants their green color, enables them to use sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide into sugars and carbohydrates, chemicals the cell uses for fuel.

Like the fungi, another kingdom of eukaryotes, plant cells have retained the protective cell wall structure of their prokaryotic ancestors. The basic plant cell shares a similar construction motif with the typical eukaryote cell, but does not have centrioles, lysosomes, intermediate filaments, cilia, or flagella, as does the animal cell. Plant cells do, however, have a number of other specialized structures, including a rigid cell wall, central vacuole, plasmodesmata, and chloroplasts. Although plants (and their typical cells) are non-motile, some species produce gametes that do exhibit flagella and are, therefore, able to move about.

Plants can be broadly categorized into two basic types: vascular and nonvascular. Vascular plants are considered to be more advanced than nonvascular plants because they have evolved specialized tissues, namely xylem, which is involved in structural support and water conduction, and phloem, which functions in food conduction. Consequently, they also possess roots, stems, and leaves, representing a higher form of organization that is characteristically absent in plants lacking vascular tissues. The nonvascular plants, members of the division Bryophyta, are usually no more than an inch or two in height because they do not have adequate support, which is provided by vascular tissues to other plants, to grow bigger. They also are more dependent on the environment that surrounds them to maintain appropriate amounts of moisture and, therefore, tend to inhabit damp, shady areas.

It is estimated that there are at least 260,000 species of plants in the world today. They range in size and complexity from small, nonvascular mosses to giant sequoia trees, the largest living organisms, growing as tall as 330 feet (100 meters). Only a tiny percentage of those species are directly used by people for food, shelter, fiber, and medicine. Nonetheless, plants are the basis for the Earth's ecosystem and food web, and without them complex animal life forms (such as humans) could never have evolved. Indeed, all living organisms are dependent either directly or indirectly on the energy produced by photosynthesis, and the byproduct of this process, oxygen, is essential to animals. Plants also reduce the amount of carbon dioxide present in the atmosphere, hinder soil erosion, and influence water levels and quality.

Plants exhibit life cycles that involve alternating generations of diploid forms, which contain paired chromosome sets in their cell nuclei, and haploid forms, which only possess a single set. Generally these two forms of a plant are very dissimilar in appearance. In higher plants, the diploid generation, the members of which are known as sporophytes due to their ability to produce spores, is usually dominant and more recognizable than the haploid gametophyte generation. In Bryophytes, however, the gametophyte form is dominant and physiologically necessary to the sporophyte form.

Animals are required to consume protein in order to obtain nitrogen, but plants are able to utilize inorganic forms of the element and, therefore, do not need an outside source of protein. Plants do, however, usually require significant amounts of water, which is needed for the photosynthetic process, to maintain cell structure and facilitate growth, and as a means of bringing nutrients to plant cells. The amount of nutrients needed by plant species varies significantly, but nine elements are generally considered to be necessary in relatively large amounts. Termed macroelements, these nutrients include calcium, carbon, hydrogen, magnesium, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, potassium, and sulfur. Seven microelements, which are required by plants in smaller quantities, have also been identified: boron, chlorine, copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, and zinc.

Thought to have evolved from the green algae, plants have been around since the early Paleozoic era, more than 500 million years ago. The earliest fossil evidence of land plants dates to the Ordovician Period (505 to 438 million years ago). By the Carboniferous Period, about 355 million years ago, most of the Earth was covered by forests of primitive vascular plants, such as lycopods (scale trees) and gymnosperms (pine trees, ginkgos). Angiosperms, the flowering plants, didn't develop until the end of the Cretaceous Period, about 65 million years ago—just as the dinosaurs became extinct.

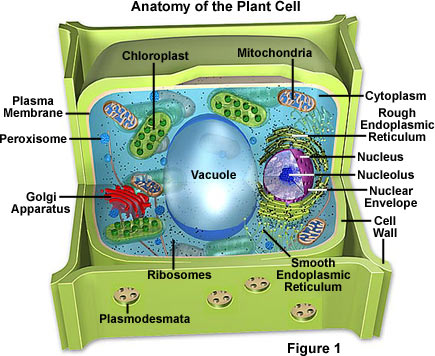

Cell Wall - Like their prokaryotic ancestors, plant cells have a rigid wall surrounding the plasma membrane. It is a far more complex structure, however, and serves a variety of functions, from protecting the cell to regulating the life cycle of the plant organism.

Chloroplasts - The most important characteristic of plants is their ability to photosynthesize, in effect, to make their own food by converting light energy into chemical energy. This process is carried out in specialized organelles called chloroplasts.

Endoplasmic Reticulum - The endoplasmic reticulum is a network of sacs that manufactures, processes, and transports chemical compounds for use inside and outside of the cell. It is connected to the double-layered nuclear envelope, providing a pipeline between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. In plants, the endoplasmic reticulum also connects between cells via the plasmodesmata.

Golgi Apparatus - The Golgi apparatus is the distribution and shipping department for the cell's chemical products. It modifies proteins and fats built in the endoplasmic reticulum and prepares them for export as outside of the cell.

Microfilaments - Microfilaments are solid rods made of globular proteins called actin. These filaments are primarily structural in function and are an important component of the cytoskeleton.

Microtubules - These straight, hollow cylinders are found throughout the cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells (prokaryotes don't have them) and carry out a variety of functions, ranging from transport to structural support.

Mitochondria - Mitochondria are oblong shaped organelles found in the cytoplasm of all eukaryotic cells. In plant cells, they break down carbohydrate and sugar molecules to provide energy, particularly when light isn't available for the chloroplasts to produce energy.

Nucleus - The nucleus is a highly specialized organelle that serves as the information processing and administrative center of the cell. This organelle has two major functions: it stores the cell's hereditary material, or DNA, and it coordinates the cell's activities, which include growth, intermediary metabolism, protein synthesis, and reproduction (cell division).

Peroxisomes - Microbodies are a diverse group of organelles that are found in the cytoplasm, roughly spherical and bound by a single membrane. There are several types of microbodies but peroxisomes are the most common.

Plasmodesmata - Plasmodesmata are small tubes that connect plant cells to each other, providing living bridges between cells.

Plasma Membrane - All living cells have a plasma membrane that encloses their contents. In prokaryotes and plants, the membrane is the inner layer of protection surrounded by a rigid cell wall. These membranes also regulate the passage of molecules in and out of the cells.

Ribosomes - All living cells contain ribosomes, tiny organelles composed of approximately 60 percent RNA and 40 percent protein. In eukaryotes, ribosomes are made of four strands of RNA. In prokaryotes, they consist of three strands of RNA.

Vacuole - Each plant cell has a large, single vacuole that stores compounds, helps in plant growth, and plays an important structural role for the plant.

Leaf Tissue Organization - The plant body is divided into several organs: roots, stems, and leaves. The leaves are the primary photosynthetic organs of plants, serving as key sites where energy from light is converted into chemical energy. Similar to the other organs of a plant, a leaf is comprised of three basic tissue systems, including the dermal, vascular, and ground tissue systems. These three motifs are continuous throughout an entire plant, but their properties vary significantly based upon the organ type in which they are located. All three tissue systems are discussed in this section.