Plasma Membrane

All living cells, prokaryotic and eukaryotic, have a plasma membrane that encloses their contents and serves as a semi-porous barrier to the outside environment. The membrane acts as a boundary, holding the cell constituents together and keeping other substances from entering. The plasma membrane is permeable to specific molecules, however, and allows nutrients and other essential elements to enter the cell and waste materials to leave the cell. Small molecules, such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and water, are able to pass freely across the membrane, but the passage of larger molecules, such as amino acids and sugars, is carefully regulated.

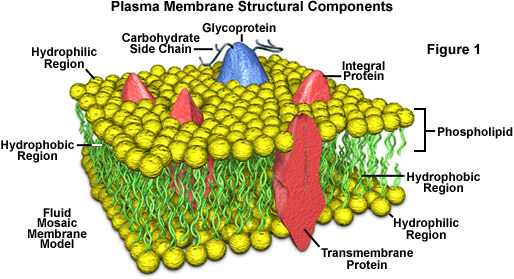

According to the accepted current theory, known as the fluid mosaic model, the plasma membrane is composed of a double layer (bilayer) of lipids, oily substances found in all cells (see Figure 1). Most of the lipids in the bilayer can be more precisely described as phospholipids, that is, lipids that feature a phosphate group at one end of each molecule. Phospholipids are characteristically hydrophilic ("water-loving") at their phosphate ends and hydrophobic ("water-fearing") along their lipid tail regions. In each layer of a plasma membrane, the hydrophobic lipid tails are oriented inwards and the hydrophilic phosphate groups are aligned so they face outwards, either toward the aqueous cytosol of the cell or the outside environment. Phospholipids tend to spontaneously aggregate by this mechanism whenever they are exposed to water.

Within the phospholipid bilayer of the plasma membrane, many diverse proteins are embedded, while other proteins simply adhere to the surfaces of the bilayer. Some of these proteins, primarily those that are at least partially exposed on the external side of the membrane, have carbohydrates attached to their outer surfaces and are, therefore, referred to as glycoproteins. The positioning of proteins along the plasma membrane is related in part to the organization of the filaments that comprise the cytoskeleton, which help anchor them in place. The arrangement of proteins also involves the hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions found on the surfaces of the proteins: hydrophobic regions associate with the hydrophobic interior of the plasma membrane and hydrophilic regions extend past the surface of the membrane into either the inside of the cell or the outer environment.

Plasma membrane proteins function in several different ways. Many of the proteins play a role in the selective transport of certain substances across the phospholipid bilayer, either acting as channels or active transport molecules. Others function as receptors, which bind information-providing molecules, such as hormones, and transmit corresponding signals based on the obtained information to the interior of the cell. Membrane proteins may also exhibit enzymatic activity, catalyzing various reactions related to the plasma membrane.

Since the 1970s, the plasma membrane has been frequently described as a fluid mosaic, which is reflective of the discovery that oftentimes the lipid molecules in the bilayer can move about in the plane of the membrane. However, depending upon a number of factors, including the exact composition of the bilayer and temperature, plasma membranes can undergo phase transitions which render their molecules less dynamic and produce a more gel-like or nearly solid state. Cells are able to regulate the fluidity of their plasma membranes to meet their particular needs by synthesizing more of certain types of molecules, such as those with specific kinds of bonds that keep them fluid at lower temperatures. The presence of cholesterol and glycolipids, which are found in most cell membranes, can also affect molecular dynamics and inhibit phase transitions.

In prokaryotes and plants, the plasma membrane is an inner layer of protection since a rigid cell wall forms the outside boundary for their cells. The cell wall has pores that allow materials to enter and leave the cell, but they are not very selective about what passes through. The plasma membrane, which lines the cell wall, provides the final filter between the cell interior and the environment.

Eukaryotic animal cells are generally thought to have descended from prokaryotes that lost their cell walls. With only the flexible plasma membrane left to enclose them, these primordial creatures would have been able to expand in size and complexity. Eukaryotic cells are generally ten times larger than prokaryotic cells and have membranes enclosing interior components, the organelles. Like the exterior plasma membrane, these membranes also regulate the flow of materials, allowing the cell to segregate its chemical functions into discrete internal compartments.