Microscope Objectives

Specifications and Identification

Identification of the properties of individual objectives is usually very easy because important parameters are often inscribed on the outer housing (or barrel) of the objective itself as illustrated in Figure 1. This figure depicts a typical 60x plan apochromat objective, including common engravings that contain all of the specifications necessary to determine what the objective is designed for and the conditions necessary for proper use.

Microscope manufacturers offer a wide range of objective designs to meet the performance needs of specialized imaging methods, to compensate for cover glass thickness variations, and to increase the effective working distance of the objective. Often, the function of a particular objective is not obvious simply by looking at the construction of the objective. Finite microscope objectives are designed to project a diffraction-limited image at a fixed plane (the intermediate image plane), which is dictated by the microscope tube length and located at a pre-specified distance from the rear focal plane of the objective. Microscope objectives are usually designed to be used with a specific group of oculars and/or tube lenses strategically placed to assist in the removal of residual optical errors. As an example, older Nikon and Olympus compensating eyepieces were used with high numerical aperture fluorite and apochromatic objectives to eliminate lateral chromatic aberration and improve flatness of field. Newer microscopes (from Nikon and Olympus) have objectives that are fully corrected and do not require additional corrections from the eyepieces or tube lenses.

Most manufacturers have now transitioned to infinity-corrected objectives that project emerging rays in parallel bundles from every azimuth to infinity. These objectives require a tube lens in the light path to bring the image into focus at the intermediate image plane. Infinity-corrected and finite-tube length microscope objectives are not interchangeable and must be matched not only to a specific type of microscope, but often to a particular microscope from a single manufacturer. For example, Nikon infinity-corrected objectives are not interchangeable with Olympus infinity-corrected objectives, not only because of tube length differences, but also because the mounting threads are not the same pitch or diameter. Objectives usually contain an inscription denoting the tube focal length as will be discussed.

There is a wealth of information inscribed on the barrel of each objective, which can be broken down into several categories. These include the linear magnification, numerical aperture value, optical corrections, microscope body tube length, the type of medium the objective is designed for, and other critical factors in deciding if the objective will perform as needed. A more detailed discussion of these properties is provided below and in links to other pages dealing with specific issues.

Manufacturer - The name of the objective manufacturer is almost always included on the objective. The objective illustrated in Figure 1 was made by a fictitious company named Nippon from Japan, but comparable objectives are manufactured by Nikon, Olympus, Zeiss, and Leica, companies who are some of the most respected manufacturers in the microscope business.

Linear Magnification - In the case of the apochromatic objective in Figure 1, the linear magnification is 60x, although the manufacturers produce objectives ranging in linear magnification from 0.5x to 250x with many sizes in between.

Optical Corrections - These are usually listed as Achro and Achromat (achromatic), as Fl, Fluar, Fluor, Neofluar, or Fluotar (fluorite) for better spherical and chromatic corrections, and as Apo (apochromatic) for the highest degree of correction for spherical and chromatic aberrations. Field curvature corrections are abbreviated Plan, Pl, EF, Achroplan, Plan Apo, or Plano. Other common abbreviations are ICS (infinity corrected system) and UIS (universal infinity system), N and NPL (normal field of view plan), Ultrafluar (fluorite objective with glass that is transparent down to 250 nanometers), and CF and CFI (chrome-free; chrome-free infinity). The objective in the illustration (Figure 1) is a plan apochromat that enjoys the highest degree of optical correction. See Table 1 for a complete list of abbreviations often found inscribed on objective barrels.

Numerical Aperture - This is a critical value that indicates the light acceptance angle, which in turn determines the light gathering power, the resolving power, and depth of field of the objective.

Mechanical Tube Length - This is the length of the microscope body tube between the nosepiece opening, where the objective is mounted, and the top edge of the observation tubes where the oculars (eyepieces) are inserted. This aspect of microscope design is discussed in more thoroughly in our mechanical tube length section of the primer. Tube length is usually inscribed on the objective as the size in number of millimeters (160, 170, 210, etc.) for fixed lengths, or the infinity symbol (¥) for infinity-corrected tube lengths. The objective illustrated in Figure 1 is corrected for a tube length of infinity, although many older objectives will be corrected for tube lengths of either 160 (Nikon, Olympus, Zeiss) or 170 (Leica) millimeters.

Cover Glass Thickness - Most transmitted light objectives are designed to image specimens that are covered by a cover glass (or cover slip). The thickness of these small glass plates is now standardized at 0.17 mm for most applications, although there is often some variation in thickness within a batch of coverslips. For this reason, some of the more advanced objectives have a correction collar adjustment of the internal lens elements to compensate for this variation. Abbreviations for the correction collar adjustment include Corr, w/Corr, and CR, although the presence of a movable, knurled collar and graduated scale is also an indicator of this feature.

Working Distance - This is the distance between the objective front lens and the top of the cover glass when the specimen is in focus. In most instances, the working distance of an objective decreases as magnification increases. Working distance values are not included on all objectives and their presence varies depending upon the manufacturer. Common abbreviations are: L, LL, LD, and LWD (long working distance), ELWD (extra-long working distance), SLWD (super-long working distance), and ULWD (ultra-long working distance). Newer objectives often contain the size of working distance (in millimeters) inscribed on the barrel. The objective illustrated in Figure 1 has a very short working distance of 0.21 millimeters.

Specialized Optical Properties - Microscope objectives often have design parameters that optimize performance under certain conditions. For example, there are special objectives designed for polarized illumination signified by the abbreviations P, Po, POL, or SF (strain-free and/or having all barrel engravings painted red), phase contrast (PH, and/or green barrel engravings), differential interference contrast (DIC), and many other abbreviations for additional applications. A list of several abbreviations, often manufacturer specific, is presented in Table 1. The apochromat objective illustrated in Figure 1 is optimized for DIC photomicrography and this is indicated on the barrel. The capital H beside the DIC marking indicates that the objective must be used with a specific DIC Wollaston prism optimized for high-magnification applications.

Objective Screw Threads - The mounting threads on almost all objectives are sized to standards of the Royal Microscopical Society (RMS) for universal compatibility. The objective in Figure 1 has mounting threads that are 20.32 mm in diameter with a pitch of 0.706, conforming to the RMS standard. This standard is currently used in the production of infinity-corrected objectives by manufacturers Olympus and Zeiss. Nikon and Leica have broken from the standard with the introduction of new infinity-corrected objectives that have a wider mounting thread size, making Leica and Nikon objectives usable only on their own microscopes. Nikon's reasoning is explained in our section describing the Nikon CFI60 200/60/25 Specification for biomedical microscopes. Abbreviations commonly used to denote thread size are: RMS (Royal Microscopical Society objective thread), M25 (metric 25-millimeter objective thread), and M32 (metric 32-millimeter objective thread).

Immersion Medium - Most objectives are designed to image specimens with air as the medium between the objective and the cover glass.

Color Codes - Microscope manufacturers label their objectives with color codes to help in rapid identification of the magnification and any specialized immersion media requirements. The dark blue color code on the objective illustrated in Figure 1 indicates the linear magnification is 60x. This is very helpful when you have a nosepiece turret containing 5 or 6 objectives and you must quickly select a specific magnification. Some specialized objectives have an additional color code that indicates the type of immersion medium necessary to achieve the optimum numerical aperture. Immersion lenses intended for use with oil have a black color ring, and those intended for use with glycerin have an orange ring, as illustrated with the objective on the left in Figure 2. Objectives designed to image living organisms in aqueous media are designated water immersion objectives with a white ring, and highly specialized objectives for unusual immersion media are often engraved with a red ring. Table 3 lists current magnification and imaging media color codes in use by most manufacturers.

Specialized Objective Designations

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 1

| Interactive Tutorial | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Some objectives specifically designed for transmitted light fluorescence and darkfield imaging are equipped with an internal iris diaphragm that allows for adjustment of the effective numerical aperture. Abbreviations inscribed on the barrel for these objectives include I, Iris, and W/Iris. The 60x apochromat objective illustrated above has a numerical aperture of 1.4, one of the highest attainable in modern microscopes using immersion oil as an imaging medium.

| Interactive Tutorial | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

The interactive tutorial linked above allows the visitor to adjust the correction collar on a microscope objective. There are some applications that do not require objectives to be corrected for cover glass thickness. These include objectives designed for reflected light metallurgical specimens, tissue culture, integrated circuit inspection, and many other applications that require observation with no compensation for a cover glass.

Objective Numerical Aperture and Working Distance

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| *Abbreviations: | Table 2 |

|

ACH, Achromat PL, Plan Achromat PL FL, Plan Fluorite PL APO, Plan Apochromat |

| Interactive Tutorial | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

To attain higher working numerical apertures, many objectives are designed to image the specimen through another medium that reduces refractive index differences between glass and the imaging medium. High-resolution plan apochromat objectives can achieve numerical apertures up to 1.40 when the immersion medium is special oil with a refractive index of 1.51. Other common immersion media are water and glycerin. Objectives designed for special immersion media usually have a color-coded ring inscribed around the circumference of the objective barrel as listed in Table 3 and described below. Common abbreviations are: Oil, Oel (oil immersion), HI (homogeneous immersion), W, Water, Wasser (water immersion), and Gly (glycerol immersion).

Objective Color Codes

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 3

Special Features - Objectives often have additional special features that are specific to a particular manufacturer and type of objective. The plan apochromat objective illustrated in Figure 1 has a spring-loaded front lens to prevent damage when the objective is accidentally driven onto the surface of a microscope slide.

Other features found on specialized objectives are variable working distance (LWD) and numerical aperture settings that are adjustable by turning the correction collar on the body of the objective as illustrated in Figure 2. The plan fluor objective on the left has a variable immersion medium/numerical aperture setting that allows the objective to be used with both air and an alternative liquid immersion medium, glycerin. The plan apo objective on the right has an adjustable working distance control (termed a "correction collar") that allows the objective to image specimens through glass coverslips of variable thickness. This is especially important in dry objectives with high numerical aperture that are particularly susceptible to spherical and other aberrations that can impair resolution and contrast when used with a cover glass whose thickness differs from the specified design value.

Although not common today, other types of adjustable objectives have been manufactured in the past. Perhaps the most interesting example is the compound "zoom" objective that has a variable magnification, usually from about 4x to 15x. These objectives have a short barrel with poorly designed optics that have significant aberration problems and are not very practical for photomicrography or serious quantitative microscopy.

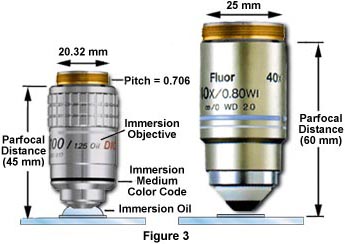

Parfocal Distance - This is another specification that can often vary by manufacturer. Most companies produce objectives that have a 45 millimeter parfocal distance, which is designed to minimize refocusing when magnifications are changed.

The objective depicted on the left in Figure 3 has a parfocal distance of 45mm and is labeled with an immersion medium color code in addition to the magnification color code. Parfocal distance is measured from the nosepiece objective mounting hole to the point of focus on the specimen as illustrated in the figure. The objective on the right in Figure 3 has a longer parfocal distance of 60 millimeters, which is the result of its being produced to the Nikon CFI60 200/60/25 Specification, again deviating from the practice of other manufacturers such as Olympus and Zeiss, who still produce objectives with a 45mm parfocal distance. Most manufacturers also make their objective nosepieces parcentric, meaning that when a specimen is centered in the field of view for one objective, it remains centered when the nosepiece is rotated to bring another objective into use.

Glass Design - The quality of glass formulations has been paramount in the evolution of modern microscope optics, and there are currently several hundred of optical glasses available for the design of microscope objectives. The suitability of glass for the demanding optical performance of a microscope objective is a function of its physical properties such as refractive index, dispersion, light transmission, contaminant concentrations, residual autofluorescence, and overall homogeneity throughout the mixture. Care must be taken by optical designers to ensure that glass utilized in high-performance objectives has a high transmission in the near-ultraviolet region and also produces high extinction factors for applications such as polarized light or differential interference contrast.

Cements employed in building multiple lens elements usually have a thickness around 5-10 microns, which can be a source of artifacts in groups that have three or more lens elements cemented together. Doublets, triplets, and other multiple lens arrangements can display spurious absorption, transmission, and fluorescence characteristics that will disqualify the lenses for certain applications.

For many years, natural fluorite was commonly used in the manufacture of fluorite (semi-apochromat) and apochromat objectives. Unfortunately, many newly developed fluorescence techniques often rely on ultraviolet excitation at wavelengths significantly below 400 nanometers, which is severely compromised by autofluorescence that occurs from natural organic constituents present in this mineral. Also, the tendency of natural fluorite to exhibit widespread localized regions of crystallinity can seriously degrade performance in polarized light microscopy. Many of these problems are circumvented with new, more advanced materials, such as fluorocrown glass.

Annealing of optical glass for the manufacture of objectives is critical in order to remove stress, improve transmission, and reduce the level of other internal imperfections. Some of the glass formulations intended for apochromat lens construction are slow-cooled and annealed for extended periods, often exceeding six months. True apochromat objectives are manufactured with a combination of natural fluorite and other glasses that have reduced transmission in the near-ultraviolet region.

Extra Low Dispersion (ED) glass was introduced as a major advancement in lens design with optical qualities similar to the mineral fluorite but without its mechanical and optical demerits. This glass has allowed manufacturers to create higher quality objectives with lens elements that have superior optical corrections and performance. Because the chemical and optical properties of many glasses are of a proprietary nature, documentation is difficult or impossible to obtain. For this reason the literature is often vague about the specific properties of glasses utilized in the construction of microscope objectives.

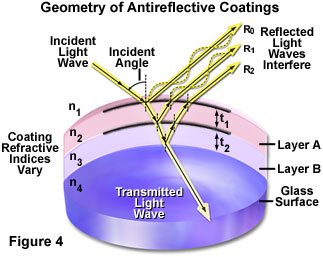

Multilayer Antireflection Coatings - One of the most significant advances in objective design during recent years is the improvement in antireflection coating technology, which helps to reduce unwanted reflections (flare and ghosts) that occur when light passes through a lens system, and ensure high-contrast images. Each uncoated air-glass interface can reflect between four and five percent of an incident light beam normal to the surface, resulting in a transmission value of 95-96 percent at normal incidence. Application of a quarter-wavelength thick antireflection coating having the appropriate refractive index can increase this value by three to four percent. As objectives become more sophisticated with an ever-increasing number of lens elements, the need to eliminate internal reflections grows correspondingly. Some modern objective lenses with a high degree of correction can contain as many as 15 lens elements having many air-glass interfaces. If the lenses were uncoated, the reflection losses of axial rays alone would drop transmittance values to around 50 percent. The single-layer lens coatings once utilized to reduce glare and improve transmission have now been supplanted by multilayer coatings that produce transmission values exceeding 99.9 percent in the visible spectral range. These specialized coatings are also used on the phase plates in phase contrast objectives to maximize contrast.

Illustrated in Figure 4 is a schematic drawing of light waves reflecting and/or passing through a lens element coated with two antireflection layers. The incident wave strikes the first layer (Layer A in Figure 4) at an angle, resulting in part of the light being reflected (R(o)) and part being transmitted through the first layer. Upon encountering the second antireflection layer (Layer B), another portion of the light is reflected at the same angle and interferes with light reflected from the first layer. Some of the remaining light waves continue on to the glass surface where they are again both reflected and transmitted. Light reflected from the glass surface interferes (both constructively and destructively) with light reflected from the antireflection layers. The refractive indices of the antireflection layers vary from that of the glass and the surrounding medium (air). As the light waves pass through the antireflection layers and glass surface, a majority of the light (depending upon the incident angle--usual normal to the lens in optical microscopy) is ultimately transmitted through the glass and focused to form an image.

Magnesium fluoride is one of many materials utilized in thin-layer optical antireflection coatings, but most microscope manufacturers now produce their own proprietary formulations. The general result is a dramatic improvement in contrast and transmission of visible wavelengths with a concurrent destructive interference in harmonically-related frequencies lying outside the transmission band. These specialized coatings can be easily damaged by mis-handling and the microscopist should be aware of this vulnerability. Multilayer antireflection coatings have a slightly greenish tint, as opposed to the purplish tint of single-layer coatings, an observation that can be employed to distinguish between coatings. The surface layer of antireflection coatings used on internal lenses is often much softer than corresponding coatings designed to protect external lens surfaces. Great care should be taken when cleaning optical surfaces that have been coated with thin films, especially if the microscope has been disassembled and the internal lens elements are subject to scrutiny.

From the discussion above it is apparent that objectives are the most important optical element of a compound microscope. It is for this reason that so much effort is invested in making sure that they are well-labeled and suited for the task at hand. We will explore other properties and aspects of microscope objectives in other sections of this tutorial.

Contributing Authors

Mortimer Abramowitz - Olympus America, Inc., Two Corporate Center Drive., Melville, New York, 11747.

Michael W. Davidson - National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 1800 East Paul Dirac Dr., The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 32310.

BACK TO ANATOMY OF THE MICROSCOPE