The Nuclear Envelope

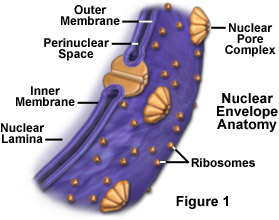

The nuclear envelope is a double-layered membrane that encloses the contents of the nucleus during most of the cell's lifecycle. The outer nuclear membrane is continuous with the membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and like that structure, features numerous ribosomes attached to the surface. The outer membrane is also continuous with the inner nuclear membrane since the two layers are fused together at numerous tiny holes called nuclear pores that perforate the nuclear envelope. These pores regulate the passage of molecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm, permitting some to pass through the membrane, but not others. The space between the outer and inner membranes is termed the perinuclear space and is connected with the lumen of the rough ER.

Structural support is provided to the nuclear envelope by two different networks of intermediate filaments. Along the inner surface of the nucleus, one of these networks is organized into a special mesh-like lining called the nuclear lamina, which binds to chromatin, integral membrane proteins, and other nuclear components. The nuclear lamina is also thought play a role in directing materials inside the nucleus toward the nuclear pores for export and in the disintegration of the nuclear envelope during cell division and its subsequent reformation at the end of the process. The other intermediate filament network is located on the outside of the outer nuclear membrane and is not organized in such a systemic way as the nuclear lamina.

The amount of traffic that must pass through the nuclear envelope on a continuous basis in order for the eukaryotic cell to function properly is considerable. RNA and ribosomal subunits must be constantly transferred from the nucleus where they are made to the cytoplasm, and histones, gene regulatory proteins, DNA and RNA polymerases, and other substances required for nuclear activities must be imported from the cytoplasm. An active mammalian cell can synthesize about 20,000 ribosome subunits per minute, and at certain points in the cell cycle, as many as 30,000 histones per minute are required by the nucleus. In order for such a tremendous number of molecules to pass through the nuclear envelope in a timely manner, the nuclear pores must be highly efficient at selectively allowing the passage of materials to and from the nucleus.