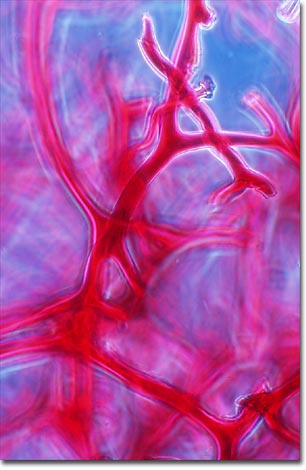

Phase Contrast Image Gallery

Sponge Skeleton

Animal, vegetable, or mineral? That was a question people entertained about sponges for thousands of years. Some sponges were hard, with either a limestone or glassy texture; others were soft and squishy. They were obviously alive because they grew branches and reproduced, but they stayed in one place, so people decided that they must be some odd form of plant.

In 1755, a few naturalists observed that if sponges weren't moving from one place to another, they were indeed moving -- an important criterion for designating an organism as an animal. Instead of these movements taking them someplace to feed, the movements brought the environment and food to the sponge. Inside these creatures, tiny flagellated cells that line inner cavities move water through the interior, allowing the sponge to filter feed on bacteria, microorganisms, and particles of organic debris. By 1765 enough scientists had observed these movements in sponges to officially designate them as animals, if very primitive and unusual animals.

Sponges have a simple cellular anatomy (not organized as tissues); an outer layer of protective, surface cells and an inner layer of flagellated cells that move water and food through the interior cavities. Between the two layers is a gelatinous material called the mesohyl (also, mesoglea or mesenchyme). Amoeboid cells move throughout the mesohyl performing different functions, such as digestion, transport of nutrients, and reproduction. Some of these cells produce structures called spicules that are scattered throughout the mesohyl to make up the skeleton of the sponge. "Skeleton" is perhaps something of a misnomer. A sponge's skeleton isn't an organized structure like a vertebrate skeleton, but an aggregation of spicules that give the animal its shape and that will persist as a structure after the sponge has died. A few species sponges lack a skeleton altogether.

Sponges are classified according to the composition of these spicules and, therefore, the skeleton. About 80 percent of sponges belong to the class Demospongiae and have a skeleton made of spongin. These are the soft elastic sponges, some of which are harvested for household and commercial use. The other 20 percent belong to the class Calcispongiae, which have spicules made of calcium carbonate, and the Hyalospongiae, which have spicules made of silicic acid. The latter are also called glass sponges because their skeletons have a glass texture. One glass sponge, the Venus Basket, grows in complex branches that, after the sponges die, are left as an exquisite and intricate glass structures that look like woven glass.

Sponges have an ancient lineage and are one of the first multicellular organisms to have occupied the Earth's oceans during the Cambrian period, 505-545 million years ago. Fossils found recently in China indicate that the sponges were well established in the Precambrian Period, at least 600 million years ago. This places the sponges well before the Cambrian explosion, which saw the remarkable increase in the number and diversity of living organisms. Nearly all sponges are marine, living in the oceans, but a few species live in freshwater habitats.

BACK TO THE PHASE CONTRAST GALLERY