Phase Contrast Image Gallery

Keloid Scars

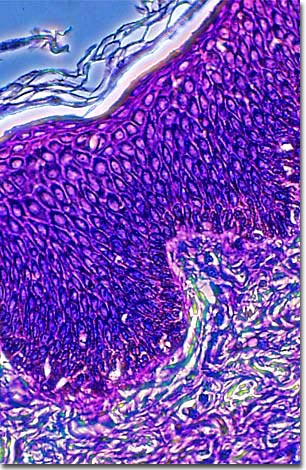

A stained thin section of human keloid scar tissue is illustrated below. As evidenced by the micrograph, combining phase contrast microscopy with classical histological staining techniques in pathological research often yields enhancement of cellular features.

When the skin is cut, burned, or otherwise damaged, it forms a scar, or cicatrix, which generally flattens and diminishes to a small white remnant over time, or disappears altogether. A keloid is a greatly enlarged scar that grows beyond its original boundaries to the point of appearing like a tumor. While not dangerous or life threatening, keloid scars may itch, cause pain or be tender to the touch. Over time, they can develop claw-like projections into the surrounding skin. In the worse cases, they can be quite disfiguring.

During the normal healing process, a scar fills with a fibrous protein known as collagen, which gives the new scar its characteristic bumpy look. With recovery, the collagen is broken down and the scar flattens and shrinks.

Keloids usually originate from an injury such a burn or severe acne, but they can also arise from minor injuries as a scratch or an insect bite. While the skin begins healing normally, something goes awry and the scar overfills with collagen, causing it to swell and enlarge.

No one understands why keloids form and they rarely respond to treatment. While surgery (traditional and cryosurgery) can remove keloids, they often return. Whatever the cause, there does appear to be a genetic component. This type of scarring is found most often in people of African and Asian origins and also seems to run in families.

One case of disappearing keloids occurred after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, Japan. People who were approximately two kilometers from ground zero of the bombing developed keloids two to three months afterwards. The keloids became most prominent six to 14 months later, but most of them shrank and healed after two years.

In the interest of self-decoration, some cultures purposefully create raised scars, or small keloids, in their skin through incisions and burning. This is practiced for aesthetic effect, religious reasons, or to indicate status or lineage.

BACK TO THE PHASE CONTRAST GALLERY