Fluorescence Digital Image Gallery

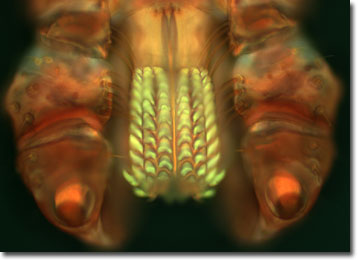

American Dog Tick

Two of the three families of ticks are capable of transmitting diseases to humans: Ixodidae, or hard ticks, and Argasidae, or soft ticks. Dermacentor variabilis, commonly known as the American dog tick belongs to the hard tick family, which also includes the deer tick (Ioxdes scapularis) and the lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum).

Hard ticks have four life stages: egg, larva, nymph and adult. Each stage requires a blood meal for morphogenesis. Preferred hosts vary by species, but most ticks will attach to almost any mammal that passes by. While feeding, a tick may stay attached to its host for hours or even days.

In the United States, ticks are the number one vector of infectious disease and are second only to mosquitoes worldwide. Hard ticks are responsible for transmitting nearly all of the major tick-borne diseases in North America. Ticks can maintain pathogens in various ways. Some microorganisms infect the eggs, which hatch into larvae, then continue through the various life stages. Other organisms are acquired by feeding on an infected host and can be transmitted to an uninfected host.

The American dog tick is one of the ticks that harbor the organism that causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever, the most common tick-borne disease in the United States. The illness was first spotted in Montana and Idaho, although it is now prevalent in the southeast. Symptoms include sudden high fevers, severe headaches, fatigue, muscle aches, nausea, and sometimes rashes. Usually symptoms become apparent 3 to 12 days after the victim has been bitten. As the organisms spread through circulation they cause bleeding of microscopic vessels that consequently can cause the vascular system to collapse, leading to death. If diagnosed early, antibiotics can cure the illness.

The specimen presented here was imaged with a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope operating with fluorite and/or apochromatic objectives and vertical illuminator equipped with a mercury arc lamp. Specimens were illuminated through Nikon dichromatic filter blocks containing interference filters and a dichroic mirror and imaged with standard epi-fluorescence techniques. The specific filter for the American dog tick was a DAPI, FITC, Texas Red combination. Photomicrographs were captured with an Optronics MagnaFire digital camera system coupled to the microscope with a lens-free C-mount adapter.

BACK TO THE FLUORESCENCE DIGITAL IMAGE GALLERY