Darkfield Microscopy Image Gallery

Butterfly Wings

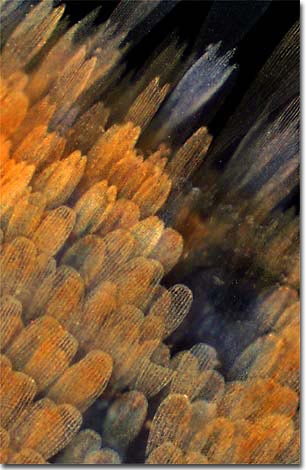

Butterflies, because of the wide spectrum of wing scale patterns exhibited by members of this order, are one of the most colorful members of the insect world. The digital image presented below illustrates a number of miniature scales that decorate most of the surface of a butterfly wing. The wing scales in this image were illuminated with a darkfield substage condenser and captured at low magnification (50x).

A network of scales covers most of the wing, giving it a beautiful array of colors produced either by pigmentation or through optical interference. The iridescent colors usually associated with butterfly wings arise from the small ridges on the scales, which interact with light causing constructive and destructive interference, much like that produced by a soap bubble. Other coloration in the wing is caused by clusters of dehydrated blood cells, leading to a wide spectrum of colors that we see as distinct patterns in the wings.

Over 160,000 species of butterflies and moths together comprise a large order of insects named Lepidoptera, which is Greek for wing scale. There are a number of similarities and differences between butterflies and moths. Most butterflies are brightly colored and fly during the day while a majority of moths have a dull and drab appearance and usually fly by night. Butterflies tend to hold their wings upright over their backs when resting, but most moths spread their wings flat near the surface when not flying. These insects also differ in the construction of their antennae. Butterfly antennae are usually long and thin and knobbed at the tip whereas moth antennae can be much more complex and often resemble feathers.

The first moths appeared about 150 million years ago during the Cretaceous period when the world was largely inhabited by dinosaurs. Butterflies evolved much later, about 40 million years ago, and many of the species alive today have evolved during the last five million years.

Butterflies and moths have a complex life cycle that consists of four separate stages. The first stage is the egg, which is fertilized during a typical insect mating ritual. Male butterflies and female moths secrete airborne pheromones that act as sexual stimulants to members of the opposite sex. In many instances, courtship is highly complicated and involves the coloration of the partners, a prenuptial courtship flight, and specialized "dances" that lead to mating. The sex attractant pheromones are complex biochemicals that probably determine most aspects of this mating behavior. Fertilized eggs are sometimes scattered by the female, but most butterflies and moths seek a suitable plant food source for their offspring. Most species lay a thousand eggs or more, but this number can vary with climate and the prevailing environmental conditions.

A short period of time after the eggs are laid, they hatch to produce caterpillars, one of the most complex and interesting stages in the life cycle of butterflies and moths. Caterpillars usually molt several times during their life by discarding their outer "skin" and forming a more elastic covering that allows expanded growth. Most of the life of a caterpillar is used to prepare for the next stage in development. They spend a majority of their time consuming nutrients to produce silk, which is used to spin a cocoon.

Caterpillars spin themselves into a silk cocoon, then transform into an immobile stage known as the pupa. During this stage, the pupa is transformed from a caterpillar into a butterfly or moth. The pupa stage can last weeks or even months, but when finished, a beautiful butterfly or functional moth breaks free from the cocoon to start the cycle again.