Spike (M.I.) Walker

Calculi (Calcium Oxalate)

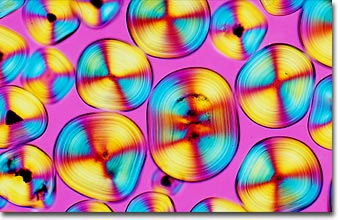

English photomicrographer Spike (M.I.) Walker has been a consistent winner of the Nikon Small World competition for many years and has published many articles and a book about microscopy. Featured below is a photomicrograph of calculi (calcium oxalate crystallites) formed in the kidneys.

|

Calculi formed in the kidneys (stones, gravel or sand according to size) are usually composed of calcium oxalate, the smallest of which are commonly termed bladder sand. Note the concentric growth layers. The photomicrograph was taken through crossed polarizers with a full-wave retardation plate inserted into the light path between the specimen and the analyzer. The objective was a planapochromat 10x/0.32 NA coupled to an achromatic condenser and mounted on a Zeiss Ultraphot III microscope equipped with an automatic 35-millimeter photohead. The film was Fujichrome Velvia. (25x) |

Kidney stones, or renal calculi, are one of the most painful and common of the urologic disorders; more than one million cases were diagnosed in 1996. Men tend to be affected somewhat more frequently than women. While the causes of kidney stones aren't entirely understood, they are not a product of modern life. Scientists have found evidence of kidney stones in a 7,000-year-old Egyptian mummy.

A renal calculus develops from crystals that precipitate from salts in the urine. Normally, urine contains chemicals that prevent the crystals from forming. These inhibitors do not seem to work effectively for all people, however, so some are more inclined to form stones than others. A nucleus for the precipitation of urinary salts can be a clump of bacteria, degenerated tissue, sloughed-off cells, or a tiny blood clot. Minerals collect around the foreign particle and encrust it. As the stone increases in size, the surface area available for additional mineral deposition is continually increased.

If the crystals remain tiny enough, they will travel through the urinary tract and pass out of the body in the urine without being noticed. Even larger stones can pass without any intervention by a physician. Stones that cause lasting symptoms or other complications may require surgery, or they may be broken into smaller pieces with sound waves in a procedure called ultrasonic lithotripsy.