Oblique Digital Image Gallery

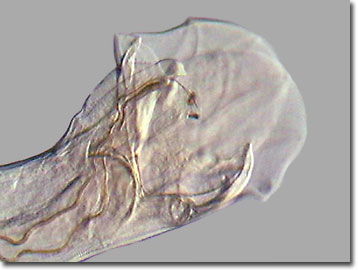

Hookworm (Ancylostoma duodenale) Copulatory Bursa

Hookworms are voracious, blood-sucking parasites from the Phylum Nematoda (roundworms), which can usually found in the intestines of their hosts. The name is derived from the hook-like appendages of the mouth (buccal cavity), which are armed with cutting plates or large teeth for piercing the intestinal wall. There are two principal species of hookworms that infect humans: Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale.

First reported in Brazil and then Texas, N. americanus is now also found in Africa, India, and Southeast Asia. The other human hookworm, A. duodenale, occurs in Africa, India, China, and other parts of Southeast Asia. Two other species of hookworms, A. caninum specific to dogs and A. tubeforme, which infests cats, have also been reported to infest humans, but fail to mature.

The larger (10 to 13 millimeters length), but shorter-lived (5 years) Ancylostoma species produce up to 25,000 eggs per day while mature females of the relatively shorter (9 to 11 millimeters length) and longer-lived (15 years) American species can release up to 9,000 eggs each day. While both species can penetrate human skin, only the non-American representative of the hookworms can infect humans via ingestion. Often bare-footed individuals walking across contaminated soil, particularly in Third World countries where sewage disposal and treatment are wanting, become infested. Because the eggs are relatively thin-walled and require moist, shaded conditions for development, these species of hookworms tend to only be found in tropical and semi-tropical climates.

Hookworms are sensitive to carbon dioxide and changes in temperature. On contact with a warm-blooded host, the nematodes penetrate rapidly into the skin. While Necator releases proteolytic enzymes from their pharyngeal glands to aid skin penetration, Ancylostoma appears to rely solely on mechanical penetration. Once in the skin, the larvae pass into the blood capillaries and then to the lungs. After migrating and molting, the parasites move into the esophagus, eventually attaching to the mucous layers of the small intestine, where they feast on blood meals. Heavy hookworm infestations can account for as much as 200 milliliters of blood loss per day, resulting in anemia, and sometimes fatalities.

Contributing Authors

Cynthia D. Kelly, Thomas J. Fellers and Michael W. Davidson - National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 1800 East Paul Dirac Dr., The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 32310.

BACK TO THE OBLIQUE IMAGE GALLERY

BACK TO THE DIGITAL IMAGE GALLERIES

Questions or comments? Send us an email.

© 1995-2025 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State University. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any manner without permission from the copyright holders. Use of this website means you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Conditions set forth by the owners.

This website is maintained by our

Graphics & Web Programming Team

in collaboration with Optical Microscopy at the

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory.

Last Modification Friday, Nov 13, 2015 at 02:19 PM

Access Count Since September 17, 2002: 25857

Visit the website of our partner in introductory microscopy education:

|

|