Darkfield Digital Image Gallery

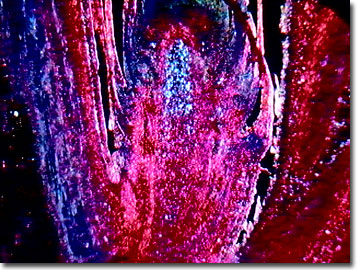

Parenchyma Abscission Layer

The abscission layer, a barrier of thin-walled parenchyma cells, develops across the stem (or petiole) at the base of a leaf, flower, or fruit as it approaches the time of falling from a plant. Abscission is the process that should be recognized for creating the beautiful autumn colors of deciduous trees in temperate regions, and this specialized layer acts as the breaking point for separating the plant from its terminal appendages.

View a low magnification image of the parenchyma abscission layer.

Leaf senescence, flower wilting, and fruit ripening are dependent on abscission, which is triggered by plant hormones. The abscission layer is comprised of minute tubules designed to transport water to the leaf, flower, or fruit and carry carbohydrates back into the tree. In the autumn, cells in the abscission secrete a waxy substance (suberin) and begin to swell, reducing the amount of nutrients and water that flow through the tubes. Without fresh raw materials, leaves cannot produce chlorophyll and the green color, which dominates trees throughout the spring and summer, fades to reveal the orange and bright yellow colors of previously masked pigments. Each leaf may display a variety of different colors during various times of the year before eventually depleting all reserves and dropping from the tree. The transformation of color is produced by internal changes occurring between the varying amounts of different pigments.

The photoperiod (the length of the night) and temperature activate changes in the abscission layer, which produce a wide spectrum of leaf colors ranging from yellow to red. In fact, urban trees influenced by the radiance of city streetlights keep their leaves longer than the same species found in darker, rural settings. A hard frost can prevent a leaf from completing its natural cycle and simply cause it to die and turn brown. Typically, the color change in leaves initiates at the outer edges of the tree and progresses inward.

In the fall, the abscission layer disappears, weakened by polysaccharides hydrolyzed by enzymes, and only the transport tubes remain to hold the leaf, flower, or fruit to the stem. A protective scar grows, so that pathogens and pests cannot enter the plant. With wind and the weight of the load exceeding the strength of the tubes, the tubes soon break, and the leaf, flower, or fruit falls to the ground.

Ethylene, the only gaseous plant hormone, is responsible for fruit ripening, growth inhibition, leaf abscission, and aging. Produce transporters have capitalized on the properties of ethylene to ship unripened fruits and artificially ripen them during transport with synthesized gas in warehouses, train boxcars, ship holds, and refrigerated trucks, guaranteeing ripe, but not rotten and bruised fruit at the marketplace. Likewise, auxins, another class of plant hormones (including indole-3-acetic acid), are sprayed on fruit trees to initiate and synchronize fruit setting from flowers and to cut down losses associated with premature dropping by inhibiting the formation of the abscission layer.

Contributing Authors

Cynthia D. Kelly, Thomas J. Fellers and Michael W. Davidson - National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 1800 East Paul Dirac Dr., The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 32310.

BACK TO THE DARKFIELD IMAGE GALLERY

BACK TO THE DIGITAL IMAGE GALLERIES

Questions or comments? Send us an email.

© 1995-2025 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State University. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any manner without permission from the copyright holders. Use of this website means you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Conditions set forth by the owners.

This website is maintained by our

Graphics & Web Programming Team

in collaboration with Optical Microscopy at the

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory.

Last Modification Friday, Nov 13, 2015 at 02:19 PM

Access Count Since September 17, 2002: 9778

Visit the website of our partner in introductory microscopy education:

|

|