Brightfield Digital Image Gallery

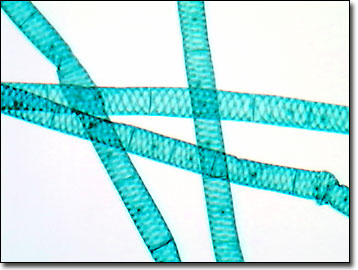

Filamentous Algae (Spirogyra)

What appears to some as mere green pond scum masks the intricate and beautiful world of filamentous algae, which is clearly visible to the microscopist and botanist. Owing its generic name, Spirogyra, to the unique manner in which members of this genus twist their green chloroplasts into spirals, this key characteristic makes it easy to recognize species in this cosmopolitan genus of the phylum Gamophyta (conjugating green algae) in the division Chlorophyta.

Often an indicator of "nutrient enrichment" (actually, over-fertilization because of excess nitrate and phosphate pollution in contaminated stormwater runoff), freshwater ponds, ditches, vernal pools, and springs are often choked with tangles of this multicellular alga. In the full sun of the day, the algal mats produce a relatively large volume of oxygen that adheres as tiny bubbles between the verdant strands, and which can boost the dissolved oxygen concentration of a microcosm above supersaturation. At night and on overcast days, the process reverses and the simple plants consume oxygen and produce carbon dioxide as a metabolic waste product of cellular respiration. When the algae occur in highly fertile waters in thick mats, wide fluctuations in the dissolved carbon dioxide and oxygen concentrations of the water column can result in rapid changes in the water's pH, causing stress or even death to obligate aquatic organisms such as fish.

There are more than 400 species in the genus worldwide, and they are distinguishable by the species-specific spores of the reproducing filaments. During times of impending environmental stress, such as extended droughts or heat waves, Spirogyra switches from asexual to sexual reproduction. Genetic material contained in isogametes is exchanged via temporary conjugating tubes between adjacent filaments, or even cells from the same filament, forming an egg-shaped, orange zygospore. The zygospore is adapted to surviving harsh conditions, with a thick cell wall, and emerges as a new algal filament once the environment is more favorable, perhaps after overwintering in the sediments. Nearly transparent, chloroplasts, pyrenoids, and nuclei housed within the Spirogyra cell wall are easily viewed under magnification, as are new cells formed by asexual cellular division that can lead to new filaments via fragmentation.

Contributing Authors

Cynthia D. Kelly, Thomas J. Fellers and Michael W. Davidson - National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 1800 East Paul Dirac Dr., The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 32310.

BACK TO THE BRIGHTFIELD IMAGE GALLERY

BACK TO THE DIGITAL IMAGE GALLERIES

Questions or comments? Send us an email.

© 1995-2025 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State University. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any manner without permission from the copyright holders. Use of this website means you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Conditions set forth by the owners.

This website is maintained by our

Graphics & Web Programming Team

in collaboration with Optical Microscopy at the

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory.

Last Modification Friday, Nov 13, 2015 at 01:19 PM

Access Count Since September 17, 2002: 32221

Visit the website of our partner in introductory microscopy education:

|

|