Brightfield Digital Image Gallery

Legume Nodules

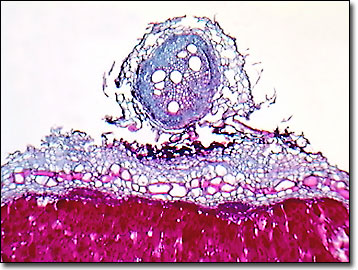

Legumes, including the many cultivated varieties of beans, peas, clovers, and alfalfa, are important as human food, livestock feed, and for restoring fertility to spent soil. Although renowned for their nitrogen-fixing abilities, it is not only the leguminous plants that add nitrates back to the soil; the partnership with symbiotic bacteria that reside on the root nodules contributes as well.

With more than 18,000 species worldwide in the family Leguminosae, plants as diverse as peanuts and ornamental mimosas have in common the characteristic seed pods that split along both sides when ripe. Whether a tree, such as the acacia, or a non-woody herb, such as the abundant yellow clover, legumes play a stellar role in human ecology and economics. For vegetarians, leguminous crops such as soybeans, fava beans and lentils provide vital sources of protein and fat, while in countries lacking electricity and refrigeration, legumes offer high nutrition coupled with favorable storage characteristics. Reaching back into human history more than 7,400 years, chickpeas, or garbanzo beans, were one of the first recorded cultivated crops. The Cyprus vetch, a legume native to the Mediterranean island, and used for livestock forage, has one of the highest convertible protein contents at 35.7 percent, while chickpeas, field beans, and peas fall within the range of 24 to 27 percent.

In the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis, the bacteria play an important role by inducing nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of the legumes. As a symbiotic or commensal relationship, the host plant provides a substrate and shelter for the soil bacteria, and the bacteria help provide required nitrates for uptake and conversion to amino acids and proteins. Recently, scientists discovered that the expression of nodulation genes in the bacteria is activated by signals from the plant roots, and in response to synthesized signals from the bacteria, the nodule meristem is activated, allowing the bacteria to enter the developing nodule. Within the plant's nodules, the bacteria induce specialized genes required for nitrogen fixation. Thus, the development and functioning of nitrifying nodules in the roots of legumes requires coevolved communications, and expression of several bacterial and plant genes. Genetic engineers are now experimenting with exploiting the symbiotic relationship between leguminous plants and their nitrifying bacteria for non-leguminous crops by inserting genes for nodulation, hoping to increase world food production while reducing reliance on expensive, petrochemical-dependent fertilizers.

Contributing Authors

Cynthia D. Kelly, Thomas J. Fellers and Michael W. Davidson - National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 1800 East Paul Dirac Dr., The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 32310.

BACK TO THE BRIGHTFIELD IMAGE GALLERY

BACK TO THE DIGITAL IMAGE GALLERIES

Questions or comments? Send us an email.

© 1995-2025 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State University. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any manner without permission from the copyright holders. Use of this website means you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Conditions set forth by the owners.

This website is maintained by our

Graphics & Web Programming Team

in collaboration with Optical Microscopy at the

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory.

Last Modification Friday, Nov 13, 2015 at 01:19 PM

Access Count Since September 17, 2002: 16786

Visit the website of our partner in introductory microscopy education:

|

|