Jan Jacbz Swammerdam

(1637-1680)

Jan Swammerdam was a seventeenth century Dutch microscopist and naturalist who is most famous for his microscopic observations and descriptions of insect development that were published posthumously as The Bible of Nature, but is more often referred to as The Book of Nature due to a mistranslation of the title. Swammerdam pioneered the use of the microscope for zoological purposes, and is considered a founder of both comparative anatomy and entomology.

Born in Amsterdam in 1637, Swammerdam was the son of a pharmacist who always wanted him to earn his living either as a practicing physician or as a member of the Calvinist ministry. Although, he trained as a medical doctor at the prestigious University of Leiden, Swammerdam preferred scientific research to the medical practice and was supported by his father for the majority of his life. In his later years, Swammerdam fell under the influence of a religious mystic, Antoinette Bourignon, and abandoned his scientific work for a time. He died in 1680 at the age of 43 from a recurrence of malaria with much of his work largely unknown and unacknowledged. Ownership rights, translation difficulties, and other complications prevented the publication of Swammerdam's collective papers until 1737, when Dutch doctor Hermann Boerhaave finished translating the opus into Latin.

There are no known paintings or other images of Swammerdam, but often a likeness taken from an oil portrait attributed to Rembrandt (like the one illustrated here), is labeled with his name. The man in the full painting is holding up a copy of Swammerdam's mayfly study, Ephemeri vita, but since the work was published in 1675 and Rembrandt died in 1669, the portrait is considered a fake. The image is most likely that of Hartmann Hartmanzoon (1591-1659) and is believed to have been lifted and reworked by the artist Jan Stolker from a Rembrandt painting of a dissection with Dr. Nicolas Tulp, head of the Leiden Medical School.

During his medical and anatomical studies, Swammerdam examined the heart, lungs, and muscles and is believed to be the first person to describe red blood cells. He also conducted important observations on how nerves function, described the anatomy of the human reproductive system, and discovered valves in the lymphatic system, which are now called Swammerdam valves. Anticipating the role of oxygen in respiration, Swammerdam suggested that air contained a volatile element that could pass from the lungs to the heart and then to the muscles, providing energy for muscle contraction.

Swammerdam's entomological work involved the life history of insects and the anatomy of mayflies, butterflies, beetles, dragonflies and bees. The first to describe the queen bee, which had previously been incorrectly referred to by scientists as the king bee, Swammerdam developed a classification of insects based on their type of development. Three of the five major groups he described are still retained in modern classification schemes. His detailed study of the development of flies via delicate dissections led him to the revolutionary conclusion that insects undergo metamorphosis through various life stages.

To aid him in his observations, Swammerdam developed a variety of original and highly effective microscopic techniques. For instance, he injected wax into specimens to hold blood vessels firm, dissected fragile structures under water to avoid destroying them, and used micropipettes to inject and inflate organisms under the microscope. Swammerdam preferred simple microscopes to compound ones and used small bead-like lenses that he made himself. He also preferred to only observe specimens under direct natural light, and his research was occasionally delayed in the fall and winter months when sunlight was scarce. Without a camera to capture images, Swammerdam made detailed drawings of his specimens and his collective microscopic work is often considered to be the most comprehensive of any single person.

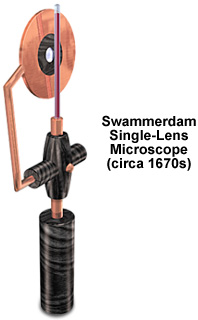

In March of 1678, Swammerdam included drawings of the microscope illustrated above in a letter to his mentor that described several experiments and observations. The single-lens microscope bears a striking resemblance to instruments made during this period by Johan Jooster van Musschenbroek in Leiden. Effectively a very small magnifying glass, the microscope is designed to be held in one hand while observing specimens. In practice microscopes having this design are very difficult to use because the specimen almost touches the lens, while the observer has to place their eye close to the lens in order to view the specimen. Typically, it is very difficult to discern much of the specimen detail. Swammerdam warned the readers of his Book of Nature that the lens:

'must, for this purpose, be carefully managed, for as it is turned one way or another, different things are seen; one cannot bring the lens nearer, or remove it further, by the least distance, but something is immediately perceived by the sight, which was not observed before.'

In his book, Swammerdam indicated that he only observed specimens visible under direct natural light, generally outdoors on summer mornings. Prior to his microscopic observation of specimens, Swammerdam carried on painstaking dissections with a variety of tools including fine pairs of scissors, a saw made from a small section of watch spring, a fine sharp-pointed pen-knife, feathers, glass tubes, small tweezers, needles and forceps. He utilized a variety of original and highly effective techniques to clean the specimen and to dissolve unwanted tissues and highlight those of interest. Without a camera to capture images, Swammerdam made drawings of his specimens, first in red crayon, then completed in black ink or pencil. Many of the drawings were ultimately transferred to copper plates for printing.

The microscope illustrated above is accompanied by a specimen holder designed to examining blood samples. The glass tube is filled with blood, which is then observed through the small bead lens mounted in ebony. A small flexible copper clasp is used to position the lens assembly with respect to the specimen for focusing. The instrument sports an ebony handle that is used to position the microscope and specimen near the observer's eye.

Contributing Authors

Matthew Cobb - Laboratoire d'Ecologie, CNRS-Université, Paris 6, Paris, France.

Shannon H. Neaves and Michael W. Davidson - National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 1800 East Paul Dirac Dr., The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 32310.