Darkfield Digital Image Gallery

Insect Spiracles

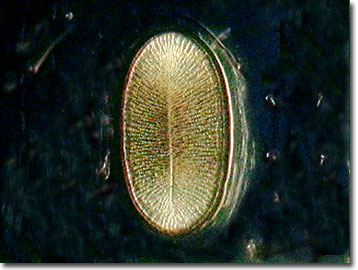

Spiracles, specialized structures featured in the class Insecta, provide the breath of life. While the tracheae constitute the respiratory system of the adult insect, spiracles are the external apertures or openings through which gases are exchanged with the environment. Usually paired, spiracles are repeated in each segment of the thorax and abdomen, one on each side.

Each spiracle connects to an elastic air tube or trachea. Tracheal breathing occurs in some invertebrates other than insects. Instead of true lungs, the tracheal system delivers oxygen to insect cells and removes carbon dioxide from the body tissues. The spiracles open into large tracheal tubes that lead to ever-finer branches, which as tracheoles, eventually penetrate to every region of the insect. At about 0.1 micrometer in diameter, tracheoles are liquid-filled and just about every cell of the insect's body is adjacent or very close to the end of a tracheole. Aquatic life poses particular challenges for this primitive breathing system. Some insects including mosquito larvae, obtain air with a specialized tracheal or breathing tube connected to the tracheal system that reaches through the surface film rather than sucking in water through the spiracles. Other insects, like water boatmen and some aquatic diving beetles, stay submerged for long periods of time using air bubbles that they carry below. An ingenious solution to the breathing problem for some insect species is to place the spiracles at the ends of sharp spines that can pierce leaves and stems and steal the oxygen directly from the photosynthesizing aquatic plants.

Valves and hairs guard the spiracles. Muscles controlling the spiracle valves enable the insect to open and close them. In dry climates for example, fruit flies avoid losing valuable body moisture by controlling the size of their spiracle openings to match the oxygen requirements of the flight muscles. During rest with less oxygen demand, the spiracles partially close. To filter out dust and other foreign material, the spiracle hairs block their entry while the insect inhales in this one-way breathing system. While smaller and less active insects operate their tracheal systems by simple diffusion, larger and more active insects, such as the grasshopper, forcibly ventilate them. It is theorized that the primitive spiracle-tracheal respiratory system is what kept insects from evolving into much larger body sizes. Because of limits to pressure that the system can handle, a dramatic increase in body weight would crush the elastic tubes that are only filled with air.

Contributing Authors

Cynthia D. Kelly, Thomas J. Fellers and Michael W. Davidson - National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, 1800 East Paul Dirac Dr., The Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, 32310.

BACK TO THE DARKFIELD IMAGE GALLERY

BACK TO THE DIGITAL IMAGE GALLERIES

Questions or comments? Send us an email.

© 1995-2022 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State University. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any manner without permission from the copyright holders. Use of this website means you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Conditions set forth by the owners.

This website is maintained by our

Graphics & Web Programming Team

in collaboration with Optical Microscopy at the

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory.

Last Modification Friday, Nov 13, 2015 at 01:19 PM

Access Count Since September 17, 2002: 21636

Visit the website of our partner in introductory microscopy education:

|

|