Lysosomes

The main function of these microscopic organelles is to serve as digestion compartments for cellular materials that have exceeded their lifetime or are otherwise no longer useful. In this regard, the lysosomes recycle the cell's organic material in a process known as autophagy. Lysosomes break down cellular waste products, fats, carbohydrates, proteins, and other macromolecules into simple compounds, which are then transferred back into the cytoplasm as new cell-building materials. To accomplish the tasks associated with digestion, the lysosomes utilize about 40 different types of hydrolytic enzymes, all of which are manufactured in the endoplasmic reticulum and modified in the Golgi apparatus. Lysosomes are often budded from the membrane of the Golgi apparatus, but in some cases they develop gradually from late endosomes, which are vesicles that carry materials brought into the cell by a process known as endocytosis.

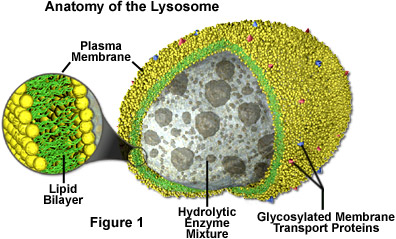

Like other microbodies, lysosomes are spherical organelles contained by a single layer membrane, though their size and shape varies to some extent. This membrane protects the rest of the cell from the harsh digestive enzymes contained in the lysosomes, which would otherwise cause significant damage. The cell is further safeguarded from exposure to the biochemical catalysts present in lysosomes by their dependency on an acidic environment. With an average pH of about 4.8, the lysosomal matrix is favorable for enzymatic activity, but the neutral environment of the cytosol renders most of the digestive enzymes inoperative, so even if a lysosome is ruptured, the cell as a whole may remain uninjured. The acidity of the lysosome is maintained with the help of hydrogen ion pumps, and the organelle avoids self-digestion by glucosylation of inner membrane proteins to prevent their degradation.

The discovery of lysosomes involved the use of a centrifuge to separate the various components of cells. In the mid-twentieth century, the Belgian scientist Christian René de Duve was investigating carbohydrate metabolism of liver cells and observed that that the cells released an enzyme called acid phosphatase in larger amounts when they received proportionally greater damage in the centrifuge. To explain this phenomenon, de Duve suggested that the digestive enzyme was encased in some sort of membrane-bound organelle within the cell, which he dubbed the lysosome. After estimating the probable size of the lysosome, he was able to identify the organelle in images produced with an electron microscope.

Lysosomes are found in all animal cells, but are most numerous in disease-fighting cells, such as white blood cells. This is because white blood cells must digest more material than most other types of cells in their quest to battle bacteria, viruses, and other foreign intruders. Several human diseases are caused by lysosome enzyme disorders that interfere with cellular digestion. Tay-Sachs disease, for example, is caused by a genetic defect that prevents the formation of an essential enzyme that breaks down complex lipids called gangliosides. An accumulation of these lipids damages the nervous system, causes mental retardation, and death in early childhood. Also, arthritis inflammation and pain are related to the escape of lysosome enzymes.