|

In a broad sense of the term, vegetable may refer to any type of plant matter. However, the word is commonly used refer to an herbaceous plant or plant portion that is cultivated for human or domestic animal food. Vegetables are a main staple in the diet of almost everyone on the planet. When fresh, they commonly consist of more than 70 percent water, but contain many nutrients and are rich in a class of biochemicals that are thought to have anti-cancer activity, the phytochemicals. Over 200 types of vegetables have been categorized around the world, with about 75 types growing throughout the United States, where over 50 types are grown commercially. Though chiefly utilized as food for humans and farm animals, some vegetables are also used for other applications, including the production of vegetable oils, starch, alcohol, and fibers.

Tomato

The differences between vegetables and fruits are not well defined. Fruits, however, are generally considered to be an edible part of a plant that contains seeds, while vegetables may include stems, roots, tubers, leaves, and other plant parts. Yet, common usage of the terms is more often based on the primary use of the item in question. For instance, tomatoes, eggplants, cucumbers, and squashes all contain seeds, so should be considered fruits, but since they do not tend to be sweet and are often eaten in salads or as a side dish like vegetables, they are frequently referred to as such. In fact, according to a decision made by the United States Supreme Court near the end of the nineteenth century, the tomato is legally a vegetable. The verdict, which forced a tomato importer to pay taxes on crops he claimed exempt because they were technically fruits, was based on the fact that the juicy items were typically served with the main part of the meal at dinner, with the soup, or as part of a course served after the soup. Today, many tomatoes are eaten alone and raw or served in juice-form, similar to other fruits, yet the controversial food remains, in a legal sense, a vegetable.

Lettuce

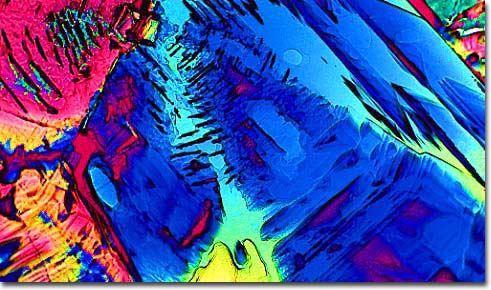

The vegetables that are commonly consumed in the United States today come from all over the world, but their true origins are not always known for certain. Scientists have a significant interest in uncovering this information, however, because of the possibility of finding other related vegetable varieties in the native area that could be used to help improve modern crops through breeding efforts. Via a variety of means, including exploration, archaeological evidence, diversity studies, and genetic evidence, many clues have been revealed regarding the native environments of certain vegetables, but others remain shrouded in mystery. Indeed, some crops have been domesticated so long that no known wild varieties exist. Nevertheless, with microscopes and sophisticated techniques, more information about the origin of plants is available than ever before. Consideration of the differences in chromosomal shape between species is an especially effective way of tracing the origins of vegetables. This information, for example, has helped scientists determine that the North American variety of maize is a direct descendant of the Central American variety, rather than the South American type.

Cauliflower

Late in the Stone Age, primitive peoples began their earliest efforts at agriculture. They presumably preferred vegetables that were easy to transport, that did not easily spoil, and which produced large amounts of durable, edible seeds that they could carry with them to new areas or which grew year after year so that food was available whenever they needed it. By favoring such plants and sowing the seeds of the best examples of these species they could find in new areas as they traveled, early humans were essentially practicing plant selection. This is how, over significant amounts of time, cultivated varieties of vegetables came to differ so greatly from wild types. For the purposes of humans, cultivated vegetables are generally superior to their wild ancestors, but in favoring certain characteristics over others, some beneficial qualities may have been lost inadvertently. However, in modern times, plant breeders have the knowledge and technology available to them that make it possible to discover new qualities or genetic factors present in vegetables, as well as the way these factors are inherited. Through their efforts, plants may be quickly improved, often in ways never thought possible in previous times. In recent years, genetic engineering has sped up the process of plant improvements to an even greater extent.

Onion

Traditionally, geneticists were only able to manipulate plants as far as their inherent genetic make-up would allow, essentially rearranging existing hereditary factors rather than creating or introducing new ones. However, modern genetic engineering, a field that is still considered in its infancy, has made it possible for new types of products, known as genetically-modified foods, to appear on grocery store shelves. These products are made by actually altering genetic material, often by introducing new genes from other plant species or organisms. The very first transgenic plant was an antibiotic-resistant tobacco plant produced in 1983, but the first genetically-modified food to become commercially available was a tomato that ripens slower than unaltered tomatoes. Since then, a number of other genetically-modified vegetables have been developed, including herbicide-resistant soybeans and maize that is tolerant of both the herbicide glufosinate and the European corn borer. Future genetically- modified products may offer even more beneficial attributes, such as extra nutritional value.

Despite certain obvious advantages of genetically-modified foods, many fear that altering vegetables and other items in this way may have unforeseen adverse long-term health effects. Scientists generally maintain, however, that eating foods with altered genes will not affect human genes and should not, therefore, be considered a health risk. Yet, consumer confidence in this assertion is apparently low since some polls have shown that as many as two-thirds of the population does not advocate genetically modifying foods. In addition to health concerns, some opponents to these new products claim that such foods should be banned simply because they are "unnatural," while others fear environmental consequences, such as the possibility of modified genes transferring to non-target species through unintended cross breeding in the fields. Meanwhile, though the controversy flourishes, many more inhabitants of the United States have consumed genetically-modified foods than realize it, primarily in the form of syrups and oils derived, in part, from altered varieties of corn or soybeans.

|