The Pesticide Collection

DDT

Interested in pesticides? Check out our Drugs for Bugs photo gallery.The term pest derives from the Latin pestis, meaning "plague," and is used to describe plants (weeds), vertebrates, insects, mites, pathogens, and other organisms that occur where we do not want them. Large agricultural endeavors have intensified the problem by concentrating a large population of pests in discrete areas. With the availability of vast quantities of succulent food and often the absence of natural enemies, pests can reproduce quickly and become a serious agricultural problem. Insects, in particular, often exhibit a dramatic and rapid increase in population size under these conditions. The average soil density of insects is about 9 million per acre with about 10,000 "in flight" above it.

Carbofuran In common usage, pesticides are usually defined as chemical agents that are used to kill pest species, although strictly speaking, biological and physical measures that can eradicate pests are pesticides as well. Oftentimes, more specific terms that reflect the primary kind of pest an agent is designed to combat are employed to describe these chemicals. Some of the most common include herbicides, which are typically applied to weeds, nematicides, which are capable of killing nematodes, fungicides, which are intended to fight fungi, and insecticides, which can eradicate insects. Although they are targeted toward eliminating different kinds of organisms, the basic ways in which these various types of pesticides function are somewhat similar. Indeed, most of the chemical agents are essentially poisons that are toxic either through contact, inhalation, or consumption. Moreover, these poisons typically gain their effect by interfering with the normal metabolic processes of the undesirable organism.

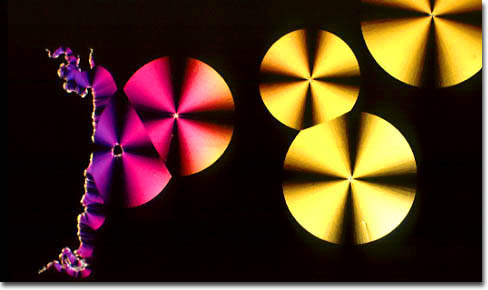

Oximino Methomal Although various means of battling pests were available in earlier periods, World Wars I and II were largely responsible for ushering into the market many of the synthetic chemical pesticides that became familiar in the following decades. Indeed, chemicals developed to promote military interests were very quickly discovered to have practical uses among the civilian population as well. The broad-spectrum insecticide DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), for instance, which is shown in the photomicrograph in the banner for this page, was discovered in 1939 and proved extremely effective at protecting troops from malaria and other insect-borne diseases overseas by killing off mosquitoes, flies, and other pests. The powerful chemical, it was soon realized, would also be useful for farmers wanting to protect their crops and even the general public, who could use the substance to help keep their own backyards free from insects. Another well-known pesticide created originally for warfare is parathion, which was discovered during German experimentation with nerve gas and was marketed as an insecticide as early as 1943.

Atrazine Due to their toxic attributes, pesticides can be dangerous for other life forms as well as the pests that they are meant to eliminate. An awareness of this danger was not widely realized, however, until the 1960s, when American biologist Rachel Carson published her watershed work Silent Spring, the title of which refers to the seemingly small number of birds that could be heard singing during the period. Carson chiefly attributed this relative silence to adverse effects on wildlife from the heavy, indiscriminate use of DDT and other members of the organochlorine class of pesticides prevalent at the time. Organochlorine pesticides are quite effective, altering both sodium and potassium concentrations in neurons, affecting impulse transmission and causing muscles to twitch spontaneously before death ensues. Yet, they also persist for a long time in the environment and bioaccumulate. Due to these and other concerns about their safety, organochlorine pesticides are gradually being phased out in many parts of the World. In fact, in the United States, DDT has been banned since the early 1970s. However, even though the agent has been restricted in the country for over 30 years, it still persists in the environment.

Chlordane In addition to potential health and environmental hazards, another problem with pesticide use has been anxiously noted-the development of pests that are resistant to the chemicals that have been traditionally used to fight them. This resistance is a byproduct of pesticide use itself, since the few insects or other pests that are naturally resistant, due to their genetic make-up, to a chemical applied to them are the only to survive. These pests are then left to reproduce with others that have also endured the chemical application, passing on the genes that hold the key to their resistance to their offspring. Since most pests reproduce at a rapid rate, resistant populations can develop at a remarkable rate in localized areas, sometimes creating problems that are more serious than those that were initially suffered from the original group of pests. Resistance to certain pesticides has been reported in hundreds of different species of insects and mites and has also appeared, though to a lesser extent, in weeds, plant pathogens, nematodes, and rodents. Despite a number of concerns, pesticides are widely utilized today. In fact, many items that are used in an average American household on a regular basis are considered pesticides, though many do not realize it. Bathroom sprays that fight mold and mildew are, for instance, pesticides, as are disinfectants, sanitizers, flea powders, various swimming pool chemicals, and many types of lawn and garden care products. Such unrestricted pesticides are believed to pose little risk of harm to those who utilize them properly, but should still be handled with care. Pesticides that are considered more hazardous are typically only available legally to those who hold special licenses or certifications. These authorizations usually require successful completion of specialized coursework and an examination. |

© 1995-2025 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State University. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any manner without permission from the copyright holders. Use of this website means you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Conditions set forth by the owners.

This website is maintained by our

|