|

The sensory perception of flavors is primarily derived from the interaction of receptors along the tongue with small organic molecules, although the sense of smell is also heavily involved. These receptors, located in the taste buds, experience only four primary sensations of taste--salty, sweet, sour, and bitter. Moreover, only certain areas of the tongue are able to detect each of these sensations. Saltiness, for instance, is detected along the sides and front of the tongue, while taste buds that are sensitive to sweetness are chiefly found at the tip, sourness on the sides, and bitterness near the back. In order for any of the taste buds to be affected by a flavor, however, the substance must be in a liquid solution, which may be provided by the production of saliva in the mouth if no other form of water is available.

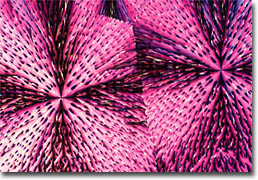

Watermelon

The flavor industry is a multi-billion dollar giant that produces chemical additives for almost every type of food on the market. Many flavors are considered natural, being derived from naturally occurring substances such as cinnamon, coffee, lemon, etc. However, the largest class of flavor molecules used today is synthetics that have no counterpart in the natural world. The development of synthetic flavors occurred in the late nineteenth century and one of the first created was synthetic vanillin, a chemical substance that imparts a taste sense similar to natural vanillin, which is just one of many chemicals found in vanilla beans. The inspiration for the creation of this substance was the fact that pure versions of real vanilla were so expensive that only a small segment of the population was able to afford them. The widespread success of synthetic vanillin motivated a number of other chemists of the period to attempt to create synthetic flavors that mimicked natural flavors.

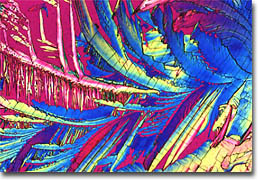

Strawberry

In addition to economic incentives, there are a number of other reasons for commercial operations to decide to utilize synthetic flavors instead of, or in conjunction with, natural flavors. Chief among these are the fact that many flavors found in nature are unstable and readily spoil. Thus, in the modern food industry, where foods may sit on shelves for many months before they are bought and consumed, it is often necessary to replace those flavor chemicals with similar substances that are more stable and safer to consume after a prolonged period of time. Also, a number of natural flavors are commonly allergenic, but synthetic versions of those flavors may be less so, thus increasing the possible market size for some synthetically flavored products. In some cases, however, synthetic flavors are chemically equivalent to their natural counterparts found in the wild. Therefore, these synthetic chemicals would have similar health effects as their natural counterparts.

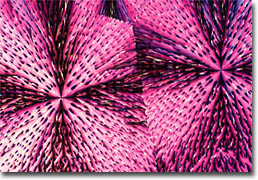

Peach

The process of creating new flavors chiefly involves a flavorist, which is a scientist that has spent a significant amount of time studying and experimenting with both natural and synthetic chemicals, plant extracts, essential oils, and other ingredients. A flavorist often works in close conjunction with a team of research chemists, who attempt to uncover new information about the precise chemical make-up of natural flavors and to discover new synthetic substances that may be of value as components of flavoring agents. A finished flavor is usually a combination of many ingredients that work together to create a certain taste sensation. For instance, if a flavorist is attempting to create the flavor of chocolate mint, several ingredients may be used to create the chocolate aspect and several others may be necessary to give the compound its minty characteristics, including the tingling sensation often associated with a natural mint flavor.

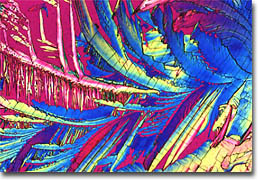

Honey

In order to ensure that a flavor achieves the proper effect, groups of tasters sample and evaluate the flavor long before the product may ever reach the market. Oftentimes these tasters are highly trained individuals that exhibit an increased awareness of the taste sensations they experience. Through the feedback they provide, flavorists are made aware of whether or not a certain flavor is essentially ready for introduction to the market or if they must go back to laboratory in order to make adjustments. Changes in flavor formulas do not necessarily mean, however, a change in the chemicals used. Flavor chemicals are very versatile in their taste properties and may be able to provide different sensations depending upon certain factors. For instance, some chemicals bestow a cherry flavor at 40 parts per million and a strawberry flavor at the higher concentration of 90 parts per million. This characteristic enables food manufacturers to reduce the size of their flavor inventory and adjust taste simply by modulating flavor concentration.

The demand for new flavors largely depends upon the amount of interest among the population in trying new things. In recent years, globalization, increased travel to foreign countries, and a proliferation of cooking shows has made many people more aware of flavors used in different parts of the world, opening up new possibilities in the flavor industry. For instance, if someone experiences a taste they enjoy in an ethnic food they sample when they are on vacation, they may want to find a sauce or a flavoring that will make it relatively simple for them to make a similar dish when they return home. Likewise, seeing someone else utilizing lots of herbs and spices on television make these items more familiar to consumers, who may be more likely to try foods that boast flavors similar to the foods they have seen prepared, even if they have never actually tasted them before. Industry experts have also found that consumers are often more apt to find a new flavor pleasing if it is associated with a food that is already familiar to them. Thus, teas that boast an array of unusual flavors are viewed with little suspicion and a favorite cookie may be received with enthusiasm when it is modified into cereal form.

|