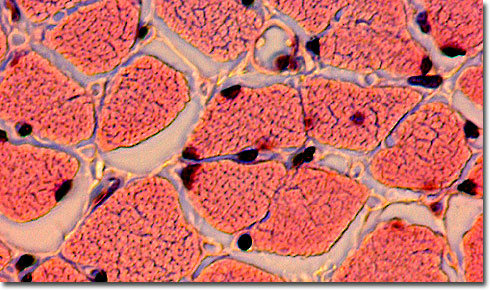

Cooked Meat Thin Section

|

In the stained thin section (eosin and hematoxylin) of cooked meat presented above, denaturation of structural protein is visible through the discontinuity in cell borders and cross striations. The nuclei of the muscle cells are still visible, but would break down if the meat were over-cooked or burned at temperatures greater than 170 degrees Fahrenheit (about 77 degrees Celsius). In other thin sections of meat, the microscopist may view bone, nerves, blood vessels, fatty tissue, and different types of muscle fibers, depending on the cut of meat and the degree of cooking. Marbleized meat, typical of corn-fattened feedlot prime steer, will show a greater degree of fatty inclusions than range beef, bison (about 25 percent less fat than domestic beef), or very lean wild venison. Veal, cut from milk-fed calves, is typically paler than most cuts of beef. Undercooked meat may display bacterial growth or harmful parasites, such as the roundworm responsible for causing trichinosis in unfortunate humans who consume improperly prepared pork. As the meat cooks, there is a physical unfolding and denaturation of the proteins in animal muscle tissue as a direct response to thermal agitation. Unstained meat goes from deep red to pale gray or brown as it cooks and the myoglobin degrades to the point at which it can no longer bind oxygen (82 degrees Celsius). As heat is applied to the raw meat, muscle fibers shorten and toughen, until the muscle structure eventually breaks down in fully cooked meat. When meat is overcooked (at temperatures greater than 71 degrees Celsius for a long period of time), the connective tissue (primarily composed of collagen) undergoes complete denaturation into a gelatin-like mass. Overall, cooked meat becomes less structured and easier to chew. Because of worries with bacterial contamination and harmful parasites in undercooked meats, color is not sufficient to judge degree of cooking, and therefore, a meat thermometer or an image captured by the light microscope may be far more reliable (although sometimes not practical). Staining for some types of bacteria will also highlight potential health problems. |

© 1995-2025 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State University. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any manner without permission from the copyright holders. Use of this website means you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Conditions set forth by the owners.

This website is maintained by our

|