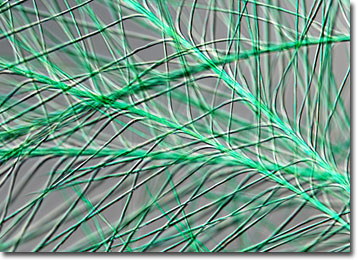

Differential Interference Contrast Image Gallery

Down Feathers

Feathers keep birds warm, help them fly, and aid in mate identification, but are also useful to humans who have been utilizing them for thousands of years. Flexible, lightweight, strong, and beautiful, the specialized epidermal growths have been utilized for diverse purposes, such as fashionable adornments, writing utensils, religious symbols, and stuffing for bedding.

All feathers are primarily composed of the fibrous protein keratin, but the size and number of feathers a bird possesses is dependent upon species. The bird with the least number of feathers is the ruby hummingbird Archilochus colubris, which features a total of 940 when in full plumage. Contrariwise, the whistling swan Cygnus columbianus may have as many as 25,000 feathers in the wintertime. The amount of feathers a bird exhibits varies by season because they are periodically molted and replaced by new growth.

There are three basic types of feathers, each with its own set of specific functions. Contour feathers line the wings, tails, and backs of birds, giving them a defined shape and acting as aerodynamic structures. Beneath them, lie the soft, fluffy feathers commonly referred to as down. As anyone who has ever used a down comforter or sleeping bag should know, down feathers are excellent insulators. Thus, their primary function is to maintain the proper body temperature of birds, a task that they are aided in by hair feathers. Sometimes alternatively known as filoplumes, hair feathers are also believed to function as pressure and vibration receptors that sense the location of other feathers so that they can be appropriately adjusted.