|

A meteorite is a mass of stony or metallic matter that survives the fall from outer space to the surface of the Earth, another planet, or one of their satellites. Meteorites hit the Earth at an estimated rate of three to four a day, although the planet is very large and is covered by so much water that very few of these falls are ever witnessed and recorded. In fact, despite their frequent occurrence, no one is known to have ever died from being struck with, or affected by the impact of, a meteorite, although in 1954, a woman was hit by one after it fell through the roof of her house and rebounded off of a radio. More commonly, meteorites fall to the ground and are never even noticed. If they are reduced to a small size due to friction with the Earth's atmosphere, the objects may not leave a noticeable crater from their impact, making it difficult to find them, especially if they fall in an area dense with other rocks, trees, or similar items. Meteorites are easiest to find on Earth in deserts and other barren landscapes, such as that of Antarctica. Meteorites are also readily identifiable, however, on the moon, where the objects are more likely to leave impact craters due to the fact that they may fall at very high speeds because the lunar atmosphere provides little resistance to slow them.

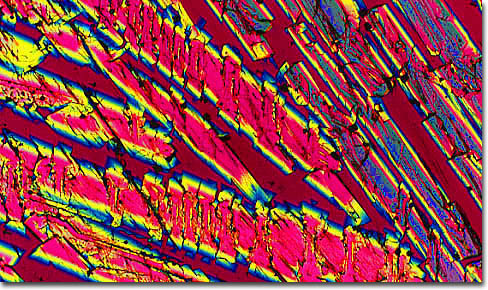

Deep Space Meteorite

Although rare, throughout the chronicled history of our planet, meteorite falls and impacts have been observed. In the past, however, these events were very poorly understood. Often they were hailed as acts of a divine being who was believed to want to punish those who were immoral, a view that was formerly applied to many other types of natural phenomena as well. Some rather considered meteorites as a sort of gift from the heavens, and held them in religious awe. In such cases, the objects were often kept in a temple, shrine, church, or other place of worship. At other times, however, the reality of objects falling from the sky was denied, and reports of such events were attributed to a form of mass hysteria. It was not until the early 1800s that it was widely accepted among the scientific community that meteorites really do fall to the planet from outer space. Since that time, the objects have been of immense scientific interest and several important discoveries have been made in regard to them.

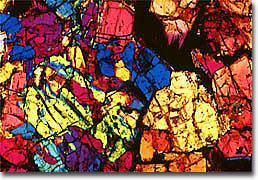

Asteroid Meteorite

Though many meteorites may have little physical effect upon the Earth, a number of large meteor impacts are known to have occurred on the planet, some of which have been associated with extensive destruction. For example, the Tunguska event that took place in Siberia in 1908 and felled trees throughout a 20-mile radius is believed to have been meteor related, although since no debris from the object was found, it has been widely assumed that the it exploded immediately before it actually hit the surface of the planet. More important, perhaps, is the evidence that a large impact occurred along the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico approximately 65 million years ago, leaving an approximately 180 kilometer-diameter crater, which has been dubbed Chicxulub, in its wake. Matter believed to have been ejected from this impact has been discovered around the world, a testament to the immense force with which the meteorite must have hit the planet. The effects of such an impact would have been devastating, likely consisting of widespread fires and possibly resulting in so much ash that global temperatures may have decreased and acid rain could have developed. Some experts believe that these and other possible effects of the impact may have hastened the extinction of the dinosaurs near the end of the Cretaceous Period.

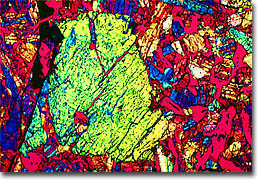

Lunar Meteorite

Meteorites derive from a variety of sources including asteroids, the moon, and other planets, as well as some that were formed during the birth of the solar system. For the purposes of classification, meteorites can be roughly divided into four categories. Over 90 percent of recovered meteorites are classified as aerolites, or stony meteorites, which consist of two classes. The chondrites are the most common stony meteorites, comprising approximately 85 percent of all meteorites recovered. Achondrites are the other principal class of stony meteorites, constituting about 7 percent of the total number of meteorites recovered. The other principal meteorites are the more rare stony-irons, also known as siderolites, which comprise approximately 1.5 percent of identified meteorites, and the siderites, or irons, that account for approximately 6 percent.

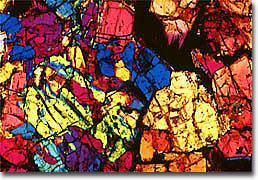

Martian Meteorite

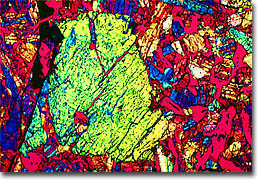

Geologists and astrogeophysicists study meteorite composition and properties to learn more about the origin and evolution of the solar system. This practice essentially began in the mid-nineteenth century when Henry Clifton Sorby first examined a thin-section of a meteorite under a microscope. Through this and other means of analysis, it is possible to determine the elements present in meteorites and their proportions, but tiny spheres of material found within certain meteorites (chondrites) are of primary interest. These glassy spheres, which are referred to as chondrules, are widely believed to have been formed at an early stage in the development of the solar system, when clusters of dust molecules floating in the solar nebula melted and then quickly cooled and solidified. Exactly what would have caused this sudden change in temperature is unknown, but is a subject of intense interest for a number of scientists. The way that chondrules came to be incorporated into meteorites, which likely reflects the way that various bodies of material came together to form the planets, has also been an area of concentrated study.

|