|

Fragrances, also known as perfumes, have been around since the beginning of civilization. They were first used in funeral rites and religious ceremonies, especially in the form of incense, which is burned to produce an aroma. Indeed, the modern word, perfume, stems from the Latin per fumum, which means "through smoke." Over time, personal use of perfumes began to become popular, especially in Greece, where floral oils were first used and even the dead were provided with a vial of their favorite fragrance to accompany them into the afterlife. The inhabitants of Rome, an empire often associated with extravagance, also thoroughly enjoyed perfumes, and the public treasury ensured that the bathhouses they used were continuously stocked with fragrances. Scents were also often applied to pets, such as dogs and horses, which were kept by Romans. After the fall of the Rome, the art of perfumery was essentially lost to Europe, but during the Crusades of the Middle Ages the knowledge was once again obtained from the East.

Bijan DNA

One of the earliest ways to create perfumes was to employ a method known as enfleurage, whereby petals of a desired flower are laid on thin layers of purified fats to extract small quantities of fragrance chemicals from within the petals. The scented fat that results, which was formerly widely utilized both as a kind of ointment and a perfume, was called pomade. Another method, said to be invented by Arabian doctor and chemist Avicenna in the tenth century, involved extracting fragrant oils from flowers by means of distillation, a procedure that continues to be commonly used in modern times. Avicenna's primary focus was apparently the rose, and the perfume he produced, which had a more delicate scent than most others that were available at the time, was known as rose water. Sometime during the Middle Ages, animal substances, including civet, musk, and castoreum, began to be utilized in perfumes as fixatives, and in the 1300s, the first alcohol-containing perfume, known as Hungary water, was designed for Elizabeth, Queen of Hungary.

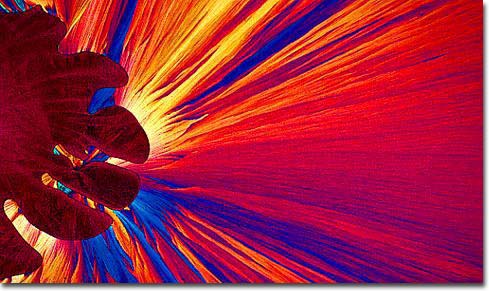

Menthol

France, a country that is today widely known for its perfume production, began to become an important player in the industry during the 1500s, after a group of perfumers from Italy settled in Paris. In fact, during her reign, Catherine de Medici maintained her own personal Italian perfumer whose workshop was linked to her own rooms via a secret passage. This clandestine setup was designed to eliminate the possibility of someone stealing the formulas created for Catherine's perfumes while they were being brought to her. Perhaps the greatest influence on modern perfumery, however, was the advent of synthetic organic chemistry in the early 1830s, when aroma chemicals, including cinnamic aldehyde from cinnamon oil and benzaldehyde from bitter almond oil, were first isolated and identified. Subsequent to 1850, more synthetics became available, such as esters of low molecular weight acids and alcohols, methyl salicylate (artificial wintergreen oil), and vanillin.

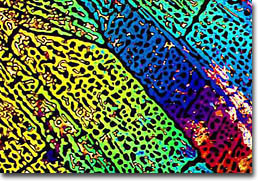

Giorgio Body Lotion

By the early twentieth century, synthetic perfumes, which were often more affordable than earlier scents, became quite common. Yet, the golden age of synthetic fragrances may really be considered to have arrived in the 1920s with the introduction of Chanel No. 5, a concocted fragrance that perfumers describe as "aldehydic" in nature. Released by fashion designer Coco Chanel, who had been associated with many of the greatest artists of her time, in a highly recognizable art deco bottle, Chanel No. 5 launched a trend that has yet to come to an end. The immense success of the perfume, which is still on the market, led to a succession of other scents produced by fashion designers, many of which are among the most popular available. A contemporary testament to this fact is the frequent occurrence of designer fragrances being "knocked-off" or copied by other manufacturers, who wish to profit from the name brand's success.

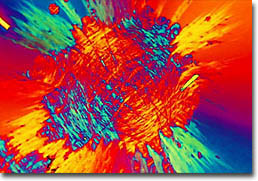

Vanillin

In the booming fragrance market today, literally thousands of manufacturers are synthesizing aromatic fragrance chemicals all around the world. The vast majority of the perfumes produced are, however, mixtures of synthetic and natural fragrances, which may add softness to the final product, as well as fixatives that may provide pungency as well as the even evaporation of scents. In liquid varieties, the ingredients are typically combined with alcohol, while in cosmetic products, soaps, deodorants, and other solids they are often combined with fatty bases. Many fine perfumes blend more than 100 different ingredients, but are often classified based on the most dominant and noticeable one or more fragrances they contain. The floral class, for instance, may smell of jasmine, rose, or lilac, while the woody group is dominated by scents such as cedarwood and sandalwood. Other key groups of perfumes may be characterized as spicy, citrus, herbal, mossy, Oriental, or aldehydic.

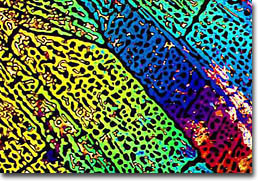

Passion Body Lotion

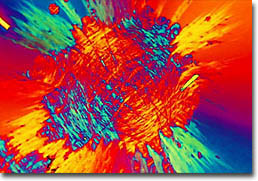

Preparing samples of fragrances for photomicrography is one of the most challenging investigations we have undertaken. Fragrances are typically small organic molecules that have extremely high vapor pressures and are very difficult to crystallize. Our photomicrographs of menthol and vanillin were relatively easy to acquire because both of these compounds are crystalline solids at room temperature. The body lotion samples shown on this page were much more difficult to prepare than purified solid crystallites (such as menthol or vanillin). They were first extracted with methylene chloride to remove organics, and then allowed to evaporate to form crystallites.

|