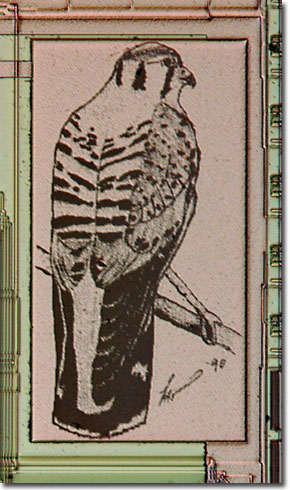

Kestrel (Sparrow Hawk) - Brightfield Illumination

|

A Hewlett-Packard design team headed by Howard Hilton in Lake Stevens, Washington was responsible for placing what is perhaps the World's smallest rendition of a kestrel (sparrow hawk) on a numerically-controlled oscillator/mixer integrated circuit. This chip contains about 180,000 transistors and was code-named Kestrel or 1FW4. Released in April 1991, the logical design was produced by Dr. John Guilford at the Hewlett-Packard Lake Stevens, Washington facility, while the physical design was crafted by Garry Petrie and Paul Nuber in Fort Collins, Colorado. The original artwork for the kestrel bird was drawn by Lynn Mahnke in 1990, and her signature (Lynn '90) appears to the right of the bird's tail feathers. The chip was loaned for imaging by Dr. John Guilford of Agilent Technologies (formerly Hewlett-Packard). View this silicon artwork under differential interference contrast and darkfield illumination. The kestrel, with a wingspread of merely 22 inches, is the only small hovering hawk found in North America. Being smaller than the related merlin (pigeon hawk) and peregrine falcon, kestrels feed mainly on insects and mice, and seldom on other birds. Females are a bit larger than their male counterparts, have an average wingspan of 24.5 inches, and a bantam weight of 4 ounces. Kestrels demonstrate sexual dichromatism, with the females displaying more subdued color tones in contrast to the brighter, rufous-colored males. Ornithologists know this tiny raptor as Falco sparverius, a species originally described by the renowned zoologist and pioneering taxonomist, Carolus Linnaeus. Taxonomists have scientifically described four subspecies for the American kestrel, which is related to the European kestrel. In north-central Florida, Southeastern American kestrels (F. s. paulus) have lost more than 80 percent of their critical habitat, and are classified by the State of Florida as a threatened species. Categorized in the family Falconidae, this bird species has acquired several common names including grasshopper hawk, mouse hawk, short-winged hawk, American kestrel, rusty-crowned falcon, windhover, and kitty hawk. It is fitting that America's aviation industry was born on a beach on the Outer Banks of North Carolina named for this agile flier. Largely migratory, American kestrels winter throughout the lower 48 states of the United States, through Mexico, and into Panama. Breeding areas range to the north into Alaska and the Northwest Territories, and east to Nova Scotia. Kestrels are generalists in their habitat preferences, and occupy nearly all types of open grassland, shrub land, and forest edges. In rural areas, kestrels are often observed perched on overhead utility lines between predatory forays over prairies and croplands. As consumers of insects and rodents, these tiny raptors should be considered important allies to farmers. Because they are cavity nesters, kestrel populations have suffered in areas where timber harvesting practices remove older trees, but the birds are willing to utilize artificial nest boxes posted on utility poles and fence posts. Exemplifying the life history pattern of being small in size, maturing quickly, and having a short life span, both sexes of the American kestrel are capable of breeding as yearlings. The breeding season of the sparrow hawk varies geographically based on climatic conditions, and pairing occurs between mates about 10 weeks before egg laying commences, resulting in a clutch size of 3 to 7 eggs. Two matings can occur per breeding season, and with an incubation period of about one month, kestrel populations can rapidly respond to increased prey availability. If a predator or storm destroys the first group of eggs, the female can lay an additional clutch. After one month, the young are ready to fledge. Although some records record kestrels living as long as 11 years, they usually don't survive past a year in age. Potential predators of American kestrels include great horned owls, golden eagles, red-tailed hawks, and prairie falcons. Nest raiding by crows and ravens, raccoons, skunks, and coyotes also takes its toll on kestrel numbers. Because kestrels depend on small mammals and insects for their diet, this avian species is susceptible to poisoning associated with pest management practices. Lower reproductive success and die-offs have resulted from the build up of pesticide residues in local kestrel populations. Habitat destruction due to over-harvesting of timber, establishment of even-age pine plantations, and forest clearing for crops and fruit orchards have eliminated much of the natural range of this miniature falcon. However, unlike many species of raptor, the American kestrel appears fairly tolerant of human disturbance. |

© 1995-2022 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State University. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any manner without permission from the copyright holders. Use of this website means you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Conditions set forth by the owners.

This website is maintained by our

|